Chaitali B Roy: From Women of Kuwait to Sadaaqa

For Chaitali B Roy, culture is not observed from a distance… it is lived, listened to, and gently translated into story. A Kuwait-based author, journalist, broadcaster and podcaster with over two decades of immersive engagement across the Gulf and India, Chaitali has built her life’s work around listening deeply, documenting gently, and preserving stories that might otherwise fade into silence. Her journalism is driven not by urgency for headlines, but by patience, trust, and an unshakeable respect for lived experience.

From her early years with HMV Saregama in India to her long-standing association with Kuwait Radio and Arab Times, Chaitali’s journey reflects a rare commitment to cultural memory, especially narratives shaped by women, migration, heritage and belonging.

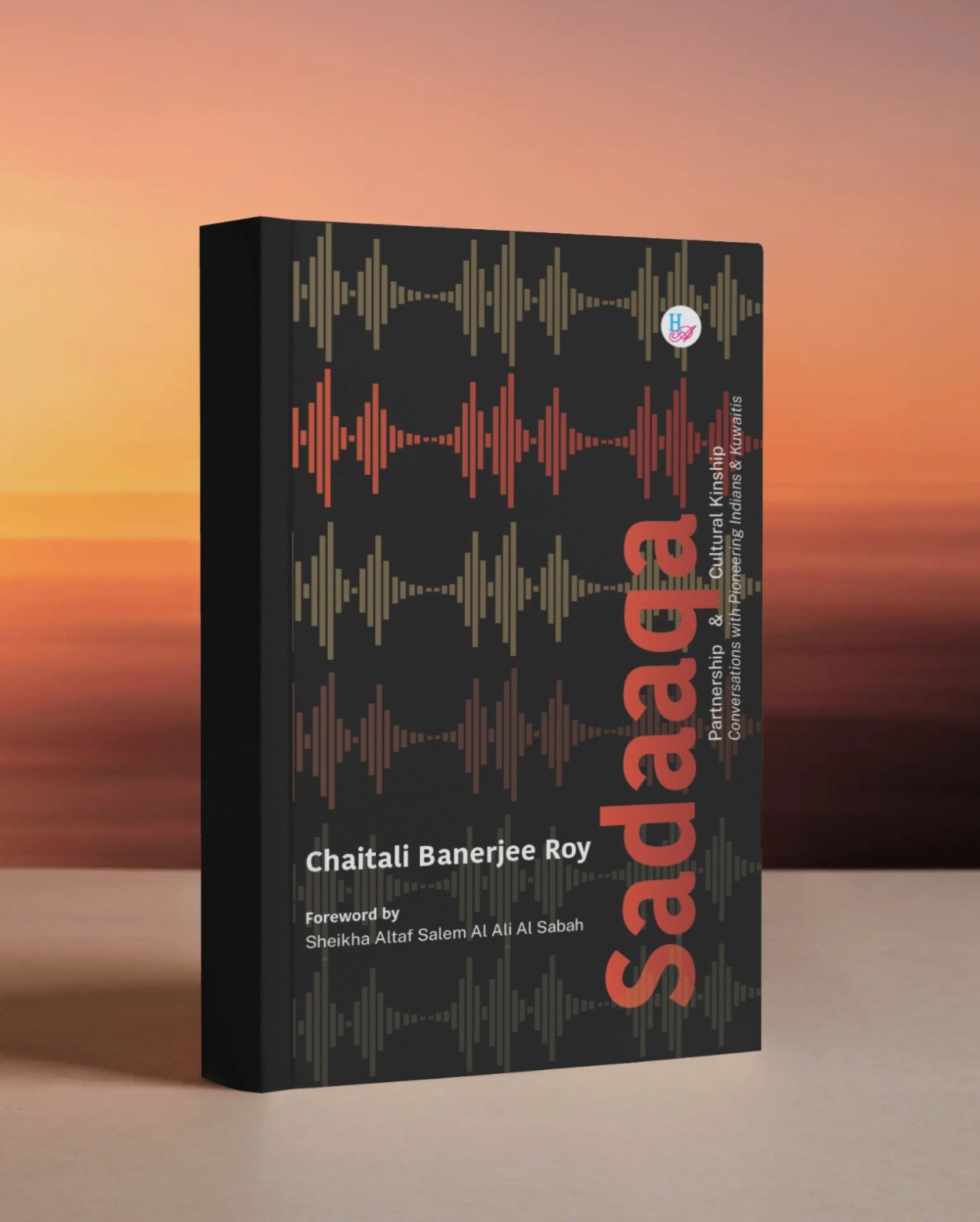

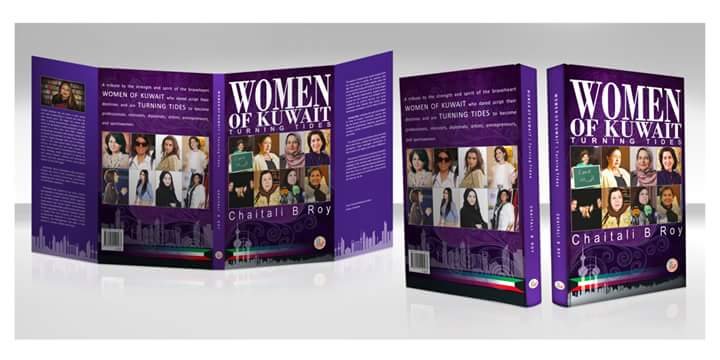

Her landmark book Women of Kuwait: Turning Tides broke new ground as the first English-language documentation of Kuwaiti women’s lives, offering intimate oral histories that dismantled stereotypes and revealed strength, agency and leadership long before they were acknowledged publicly. That same sensitivity carries into Sadaaqa, a work born from years of personal recollection, family archives and quiet conversations, where Indo–Kuwaiti history is explored not as a transaction of labour or trade, but as a shared civilisational journey shaped by affection, influence and mutual respect. Across her books, radio shows and podcasts, Chaitali’s voice remains consistent: thoughtful, restrained and deeply humane, guided by the belief that stories are not to be exposed, but honoured.

In an exclusive interview with Sumita Chakraborty, Founder & Editor-in-chief, TheGlitz, the immensely talented Chaitali B Roy opens up about her books Sadaaqa and Women of Kuwait: Turning Tides – memory, migration, silence, trust and the responsibility of preserving stories that sit at the intersection of history and heart… offering rare insight into a life devoted to cultural truth-telling with grace and integrity.

Over to the Multi-faceted Chaitali B Roy

Sadaaqa draws heavily from personal recollections and family archives. Firstly, what made you want to pen this book? In an era where cultural memory is fast eroding, what was the biggest challenge in preserving these oral histories with authenticity and emotional accuracy?

Chaitali: Very early in Kuwait, I realised how deep the connection between India and Kuwait truly is, not just culturally, but historically and emotionally. Initially, I wasn’t thinking of writing another book. Instead, I wanted to create an audio-visual program that documented this unique relationship. The idea was to visually archive the memories of people whose lives, in different ways, represented the long-standing bond between the two countries. That initiative eventually evolved into Sadaaqa, and later into this book.

Another motivation for writing this book was to counter the limited perception that younger Kuwaitis sometimes have of Indians. There exists a stereotype, especially among younger Kuwaitis, that Indians are primarily domestic workers, drivers or nannies. With full respect to those professions, this stereotype erases an entire history of Indian contributions to Kuwait’s development. There are Indian business families, doctors, educators, bankers, administrators and pioneering professionals who built institutions, created livelihoods and shaped modern Kuwait. I wanted this book to address that narrative.

The greatest challenge has been time. Many Kuwaitis who lived in India, or whose parents and grandparents did, have already passed on. Present-day Kuwaitis often know little about that chapter of their family history. With every passing year, more stories disappear, and I felt an urgency to capture what was left.

A second challenge has been cultural sensitivity. Both ways. Kuwaitis are very private, and many Indians living here are cautious about what they share. Indian expatriates may hesitate to speak openly, sometimes out of personal discretion, sometimes due to social or professional boundaries. There are subjects that people do not want to discuss publicly, and as someone living here, I must acknowledge those limits. As someone who has lived in Kuwait for over twenty-one years, I understand these boundaries.

You highlight both Indian and Kuwaiti families who have shaped the Indo–Gulf relationship. Which story… or silence… was the most difficult for you to uncover, and why?

Chaitali: Many well-known Kuwaiti families had deep historical links with India. Some of these families had lived in India for generations, intermarried, built businesses, and sent their children to Indian schools. They carried emotional, linguistic and even culinary memories. But when I attempted to document those histories, I did meet hesitation at times. And I realised that the silence was revealing. Many families benefited from India at a time when Kuwait was still forming its identity, but some of them prefer not to speak openly about that chapter today. That reluctance is not hostility. Perhaps it stems from pride, privacy, or even the discomfort of revisiting a period when the family was not as established, not as secure, or not as powerful.

On the Indian side, the silence is of a very different nature. I met individuals who built strong businesses from nothing – people who arrived with a suitcase and a promise, and they now own very successful companies. When I asked about their challenges, the response was restrained. So, the most challenging stories were not dramatic revelations, but the occasional silence. This is especially true for second-generation Indians who belong emotionally but cannot belong legally. They speak of Kuwait with affection. This place shaped them. But they always live in a state of impermanence. Sometimes, the story lies in what people are not willing to share but in what they cannot.

Kuwaitis are known to be intensely private. What do you believe made them trust you with intimate parts of their histories, and how did you navigate ethical boundaries while documenting them?

Chaitali: Kuwaitis are indeed intensely private, and gaining access to their personal histories is not easy. I built this trust over more than two decades of living and working in Kuwait. Since arriving in 2001, I have engaged closely with local communities through journalism, cultural work, and personal relationships. During this time, I have learnt that in Kuwait, trust is earned slowly, consistently, and through sincerity of intention.

My first book, Women of Kuwait: Turning Tides, was the real turning point. I entered a space that had not been explored by an expatriate, especially not by an Indian woman or even, for that matter, by a Kuwaiti. Yet Kuwaiti women opened their homes, stories and vulnerabilities to me. They did so because I approached their narratives with deep respect. I never sensationalised any issue. I handled their stories responsibly. That became my credibility.

When I began Sadaaqa, many families already knew me as someone who would protect their dignity. They were confident that their narratives would not be altered, appropriated, or used to provoke controversy. These are families for whom legacy matters, and privacy is linked to honour.

In terms of navigating ethical boundaries, my guiding principle was simple: whenever a detail felt too personal or potentially hurtful, I navigated it carefully. I also remained conscious that expatriate experiences, especially Indian ones, carry layers of vulnerability. So, I documented these with care, discretion, and empathy. Ultimately, I think they trusted me because they knew that my intention was to preserve, not to probe and understand; not to expose but to honour. And that is a responsibility very dear to me.

The Indo–Gulf relationship is often reduced to economics, labour, and trade statistics. How does Sadaaqa challenge this narrative and push readers to confront the deeper cultural truths that have long been overlooked?

Chaitali: That question is critical because limiting the Indo–Gulf relationship to labour, economic, and trade statistics offers only the most superficial understanding of what is, in fact, a civilizational connection. But yes, trade was historically the starting point and my research confirms that the earliest interactions go back to Indus Valley civilisation and the Dilmun civilisation in present-day Bahrain and Failaka. But to look only at transactions is to miss the deeper cultural currents that have shaped people, identities and lived experiences across centuries. Sadaaqa attempts to address this perspective.

The book reveals that movement between the two regions was not simply economic migration. Indian families settled across the Gulf, particularly from western India; many assimilated so completely that their descendants today are Arab by identity, yet their surnames still echo an Indian past. Through them travelled ideas, languages, textiles, food, aesthetics, and even philosophical systems. What Sadaaqa challenges is the assumption that the relationship is one-directional or recent. The exchange has always been mutual.

Arabs have influenced Indian communities as much as Indians have shaped Gulf life. When you examine music traditions like sawt, patterns in language, household items, or even ingredients used in Kuwaiti kitchens, you see clear evidence of deep-rooted cultural borrowing. And vice versa. You see Arab influences in our food, language, music, architecture etc. Today, there are nearly one million Indians in Kuwait. They contribute significantly to economic life, but they also carry memory, craft, heritage and intergenerational stories. By highlighting the human and cultural dimension to Indo–Gulf relations, the book asks readers to look beyond numbers, beyond salaries and remittances, and recognise a shared civilisational journey. Without acknowledging that, the story remains incomplete and deeply misunderstood.

Sheikha Shaikha Al Sabah’s Padma Shri recognition represents a cultural bridge few have spoken about. What do her contributions and their reception reveal about the evolving identity of Kuwait in a rapidly changing Gulf?

Chaitali: Sheikha Shaikha Al Sabah’s Padma Shri represents far more than personal accomplishment; it marks a cultural bridge that Kuwait has rarely articulated publicly. Interestingly, Shaikha is a member of Kuwait’s ruling family.

Yoga has had an unusual journey in the Middle East. Historically, the Arab world has known of, and even engaged with, yogic traditions for centuries. As early as the 11th century, Al-Biruni, one of the greatest intellectuals of the Islamic world, spent over a decade in India studying Sanskrit, Indian philosophy, and Patanjali’s teachings. His translation of the Yoga Sutras into Arabic opened an important philosophical window into yogic thought. Later, elements of hatha yoga even found resonance in Sufi meditative practices.

Yet, in contemporary times, yoga has not always been fully embraced. There were periods in the GCC when yoga was misunderstood and seen as an extension of religious practice rather than as a science of well-being. In fact, pockets of resistance remained in the region until recently. This makes Sheikha Shaikha’s journey more significant.

Shaikha introduced yoga to Kuwait not as ideology, but as healing. Deeply private, knowledgeable, and committed to her own learning, she experienced its benefits personally before choosing to offer it to the community. When she established Dar Atma-Kuwait’s first licensed yoga studio, she did so quietly. Her description of her first experience of yoga – “like having a tall glass of cold water on a thirsty day”- captures both the intensity and sincerity of her relationship with the practice. For nearly a decade, she has trained teachers, built a community of practitioners, and advocated the philosophy of balance, clarity, and self-awareness. Through Dar Atma, yoga has transitioned from being seen as “foreign” to becoming part of Kuwait’s contemporary wellness culture.

Her Padma Shri, therefore, signifies two shifts. First, it acknowledges that wellness, spirituality, and intellectual exchange have always transcended borders. Yoga did not “arrive” today; it has existed in Kuwait quietly for decades, even within influential families. What changed is that someone presented it openly and responsibly.

Second, it reflects Kuwait’s evolving identity today. Across the Gulf, particularly among younger generations, cultural confidence is growing, allowing engagement with global practices without feeling the need to relinquish heritage. Saudi Arabia’s national yoga team recently won medals internationally; Gulf cities have opened licensed studios; and leaders openly speak about yoga – it signals a region comfortable integrating world knowledge into its own framework.

Sheikha Shaikha stands at that intersection: rooted and deeply respectful of both cultures. Her recognition is not just a personal milestone; it suggests a Kuwait that is increasingly comfortable embracing diverse forms of knowledge on its own terms.

Your work spans more than two decades of documenting cultural ties. What moments during your research made you acutely aware of how migration and diaspora reshape both belonging and identity across generations?

Chaitali: Yes, my work over the past two decades has shown me how migration shapes identity, but that experience in Kuwait is layered with a different complexity. Unlike countries where migration leads to eventual citizenship or long-term settlement, Kuwait presents a paradox — people may build lives here. Yet, the laws do not allow expatriates to belong fully.

Take the example of families who arrived decades ago, some soon after the partition of India. They built businesses, established institutions, contributed to healthcare, education, media, and commerce, yet their belonging remains emotional rather than legal. There were moments in my research that starkly captured this contrast. I met second-generation Indians who were born here, educated here, and knew no other home, but their identity is marked by impermanence, of not belonging legally. What struck me was not frustration, but a quiet acceptance of this reality.

Migration in Kuwait creates a different form of belonging, not rooted in citizenship but in contribution. Over time, these families developed a relationship with Kuwait that is deeply affectionate but also transient. Their businesses, friendships, memories and experiences are rooted here, but their sense of future remains elsewhere. These kinds of stories made me realise that diaspora identity here is defined not by ownership, but by impact.

Sadaaqa documents this unique emotional geography. It shows how migration in Kuwait reshapes identity without promising permanence. People adapt, grow, and contribute despite knowing that the country will never legally be theirs. And perhaps that is why their attachment is so poignant. It is love without entitlement, belonging without possession, and contribution without the expectation of permanence. That, to me, is one of the most powerful human truths revealed through this journey.

In today’s politically polarised world, narratives of harmony and kinship are often dismissed as idealistic. Were there moments when you confronted uncomfortable histories or tensions within the Indo–Gulf dynamic, and how did you choose to portray them?

Chaitali: Yes, there were moments when uncomfortable truths surfaced- stories of displacement, emotional uncertainty and the feeling of belonging without ever being able to claim belonging. In Kuwait, expatriates contribute significantly yet remain temporary, and that reality can be painful across generations. On the Kuwaiti side too, there were occasional hesitations in revisiting older histories. However, I chose not to over emphasize these tensions. Instead, I allowed silence, pauses and omissions to speak for themselves. Rather than exposing vulnerability, I focused on context, how migration, identity and contribution shaped people’s realities.

As your first book Women of Kuwait, received significant institutional recognition, what pressures… or freedoms, did you feel while creating Sadaaqa, especially knowing it might become a key cultural archive for future generations?

The real pressure for me was not artistic or intellectual. It was financial. I knew Sadaaqa needed time and production support, and for a long while, I continued the show without external backing. The urgency came from knowing that memories were fading, people were ageing, and I could not afford to wait indefinitely.

The freedom, however, came from already having credibility through my first book. I did not feel the need to prove myself; I was driven purely by the responsibility of preserving a shared history.

What would you say are your three milestones while writing this book?

Chaitali: The first milestone, without doubt, was being able to begin this project at all. I had been thinking about documenting Indo–Kuwaiti relationship almost immediately after my first book was published in 2016–17, but it wasn’t easy to execute. A show like this requires support, technical expertise, and a team that understands the subject’s sensitivity. I knew the people I wanted to collaborate with, but I initially found little encouragement. So simply getting the project off the ground was, for me, a significant milestone.

The second milestone was receiving the foreword from Sheikha Altaf Salem Al Ali Al Sabah. It was significant not just because she is an important figure, but because I have admired her for over two decades. She was part of my first book, and she has been a guiding presence in my professional journey. Her agreeing to write the foreword was deeply validating, and I will cherish it always.

The third milestone came when the project found its audience. With every interview recorded, every episode aired, and finally with the manuscript taking shape, I began to see how deeply the narratives resonated with people on both sides- Indian and Kuwaiti. This realisation that these stories were not just documentation but lived memory and shared heritage was very uplifting. The fact that these stories will be preserved for future generations is, for me, the true achievement.

Could you briefly tell us a bit about your first book Women of Kuwait: Turning Tides?

Chaitali: My first book Women of Kuwait: Turning Tides, was the first English-language work of its kind in Kuwait. It documented the journeys of Kuwaiti women who shaped the country’s social, cultural, and intellectual landscape. When I first arrived in Kuwait, I came with my own assumptions about the region and its women, but the reality I discovered was very different. Kuwaiti women have historically been powerful. Long before they gained political rights, they held homes and communities together when men were away at sea for months, managing finances, family, and social responsibilities single-handedly. That strength simply evolved into a different form in modern Kuwait.

What began as a journalistic curiosity eventually became a three-year radio series and then a book. I met women from diverse fields-scientists, ministers, diplomats, athletes, activists, designers and what struck me was the clarity with which they pursued their aspirations despite limitations. Their journeys challenged the stereotype of Gulf women as passive or confined, and presented a narrative grounded in agency, intellect, and ambition.

The book is built on oral histories, which makes it deeply personal. Many of the women entrusted me with private, formative experiences. When the book was published, it was received very well, and I was honoured that it eventually reached institutions like Princeton and Stanford University libraries. That validation meant a great deal not only to me, but also to the voices documented.

Turning Tides remains very close to my heart because it not only broke stereotypes but also preserved narratives that might otherwise never have been written down. It is an ongoing journey. I hope to follow it up with a companion work focusing on younger women. But it felt like the right moment to shift attention to another equally important cultural story.